Started by the youngest members of the Deep Learning Mafia [1], namely

Yann LeCun and

Yoshua Bengio, the ICLR conference is quickly becoming a strong contender for the single

most important venue in the Deep Learning space. More intimate than NIPS and less benchmark-driven than CVPR, the world of ICLR is arXiv-based and moves fast.

Today's post is all about ICLR 2016. I’ll highlight new strategies for building deeper and more powerful neural networks, ideas for compressing big networks into smaller ones, as well as techniques for building “deep learning calculators.” A host of new artificial intelligence problems is being hit hard with the newest wave of deep learning techniques, and from a computer vision point of view, there's no doubt that

deep convolutional neural networks are today's "master algorithm" for dealing with perceptual data.

Deep Powwow in Paradise? ICLR 2016 was held in Puerto Rico.

Whether you're working in Robotics, Augmented Reality, or dealing with a computer vision-related problem, the following summary of ICLR research trends will give you a taste of what's possible on top of today's Deep Learning stack. Consider today's blog post a reading group conversation-starter.

Part I: ICLR vs CVPR

Part II: ICLR 2016 Deep Learning Trends

Part III: Quo Vadis Deep Learning?

Part I: ICLR vs CVPR

Last month's International Conference of Learning Representations, known briefly as ICLR 2016, and commonly pronounced as “eye-clear,” could more appropriately be called the

International Conference on Deep Learning. The ICLR 2016 conference was held May 2nd-4th 2016 in lovely Puerto Rico. This year was the 4th installment of the conference -- the first was in 2013 and it was initially so small that it had to be co-located with another conference. Because it was started by none other than the Deep Learning Mafia, it should be no surprise that just about everybody at the conference was studying and/or applying Deep Learning Methods. Convolutional Neural Networks (which dominate image recognition tasks) were all over the place, with LSTMs and other Recurrent Neural Networks (used to model sequences and build "deep learning calculators") in second place. Most of my own research conference experiences come from CVPR (Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition), and I've been a regular CVPR attendee since 2004. Compared to ICLR, CVPR has a somewhat colder, more-emprical feel. To describe the difference between ICLR and CVPR, Yan LeCun, quoting

Raquel Urtasun (who got the original saying from

Sanja Fidler), put it best on Facebook.

CVPR: What can Deep Nets do for me?

ICLR: What can I do for Deep Nets?

The ICLR 2016 conference was my first official powwow that truly felt like a close-knit "let's share knowledge" event. 3 days of the main conference, plenty of evening networking events, and no workshops. With a total attendance of about 500, ICLR is about 1/4 the size of CVPR. In fact, CVPR 2004 in D.C. was my first conference ever, and CVPRs are infamous for their packed poster sessions, multiple sessions, and enough workshops/tutorials to make CVPRs last an entire week. At the end of CVPR, you'll have a research hangover and will need a few days to recuperate. I prefer the size and length of ICLR.

CVPR and NIPS, like many other top-tier conferences heavily utilizing machine learning techniques, have grown to gargantuan sizes, and paper acceptance rates at these mega conferences are close to 20%. It not necessarily true that the research papers at ICLR were any more half-baked than some CVPR papers, but the amount of experimental validation for an ICLR paper makes it a different kind of beast than CVPR. CVPR’s main focus is to produce papers that are ‘state-of-the-art’ and this essentially means you have to run your algorithm on a benchmark and beat last season’s leading technique. ICLR’s main focus it to highlight new and promising techniques in the analysis and design of deep convolutional neural networks, initialization schemes for such models, and the training algorithms to learn such models from raw data.

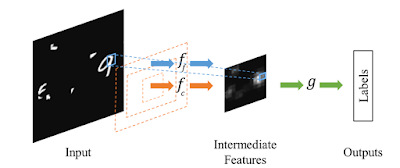

Deep Learning is Learning Representations

Yann LeCun and Yoshua Bengio started this conference in 2013 because there was a need to a new, small, high-quality venue with an explicit focus on deep methods. Why is the conference called “Learning Representations?” Because the typical deep neural networks that are trained in an end-to-end fashion actually learn such intermediate representations. Traditional shallow methods are based on manually-engineered features on top of a trainable classifier, but deep methods learn a network of layers which learns those highly-desired features as well as the classifier. So what do you get when you blur the line between features and classifiers? You get representation learning. And this is what Deep Learning is all about.

ICLR Publishing Model: arXiv or bust

At ICLR, papers get posted on arXiv directly. And if you had any doubts that arXiv is just about the single awesomest thing to hit the research publication model since the Gutenberg press, let the success of ICLR be one more data point towards enlightenment. ICLR has essentially bypassed the old-fashioned publishing model where some third party like Elsevier says “you can publish with us and we’ll put our logo on your papers and then charge regular people $30 for each paper they want to read.” Sorry Elsevier, research doesn’t work that way. Most research papers aren’t good enough to be worth $30 for a copy. It is

the entire body of academic research that provides true value, for which a single paper just a mere door. You see,

Elsevier, if you actually gave the world an exceptional research paper search engine, together with the ability to have 10-20 papers printed on decent quality paper for a $30/month subscription, then you would make a killing on researchers and I would endorse such a subscription. So ICLR, rightfully so, just said fuck it, we’ll use arXiv as the method for disseminating our ideas.

All future research conferences should use arXiv to disseminate papers. Anybody can download the papers, see when newer versions with corrections are posted, and they can print their own physical copies. But be warned:

Deep Learning moves so fast, that you’ve gotta be hitting refresh or arXiv on a weekly basis or you’ll be schooled by some grad students in Canada.

Attendees of ICLR

Google DeepMind and Facebook’s FAIR constituted a large portion of the attendees. A lot of startups, researchers from the Googleplex, Twitter, NVIDIA, and startups such as Clarifai and Magic Leap. Overall a very young and vibrant crowd, and a very solid representation by super-smart 28-35 year olds.

Part II: Deep Learning Themes @ ICLR 2016

Incorporating Structure into Deep Learning

Raquel Urtasun from the University of Toronto gave a talk about Incorporating Structure in Deep Learning. See

Raquel's Keynote video here. Many ideas from structure learning and graphical models were presented in her keynote. Raquel’s computer vision focus makes her work stand out, and she additionally showed some recent research snapshots from her upcoming CVPR 2016 work.

One of Raquel's strengths is her strong command of geometry, and her work covers both learning-based methods as well as multiple-view geometry. I strongly recommend keeping a close look at her upcoming research ideas. Below are two bleeding edge papers from Raquel's group -- the first one focuses on soccer field localization from a broadcast of such a game using branch and bound inference in a MRF.

Raquel's new work. Soccer Field Localization from Single Image. Homayounfar et al, 2016.

Soccer Field Localization from a Single Image.

Namdar Homayounfar, Sanja Fidler, Raquel Urtasun. in arXiv:1604.02715.

The second upcoming paper from Raquel's group is on using Deep Learning for Dense Optical Flow, in the spirit of

FlowNet, which I discussed in my

ICCV 2015 hottest papers blog post. The technique is built on the observation that the scene is typically composed of a static background, as well as a relatively small number of traffic participants which move rigidly in 3D. The dense optical flow technique is applied to autonomous driving.

Deep Semantic Matching for Optical Flow. Min Bai, Wenjie Luo, Kaustav Kundu, Raquel Urtasun. In arXiv:1604.01827.

Reinforcement Learning

Sergey Levine gave an excellent Keynote on deep reinforcement learning and its application to Robotics[3]. See

Sergey's Keynote video here. This kind of work is still the future, and there was very little robotics-related research in the main conference. It might not be surprising, because having an assembly of robotic arms is not cheap, and such gear is simply not present in most grad student research labs. Most ICLR work is pure software and some math theory, so a single GPU is all that is needed to start with a typical Deep Learning pipeline.

An army of robot arms jointly learning to grasp somewhere inside Google.

Take a look at the following interesting work which shows what Alex

Krizhevsky, the author of the legendary 2012 AlexNet paper which rocked the world of object recognition, is currently doing. And it has to do with Deep Learning for Robotics, currently at Google.

Learning Hand-Eye Coordination for Robotic Grasping with Deep Learning and Large-Scale Data Collection Sergey Levine, Peter Pastor, Alex Krizhevsky, Deirdre Quillen. In arXiv:1603.02199.

For those of you who want to learn more about Reinforcement Learning, perhaps it is time to check out

Andrej Karpathy's Deep Reinforcement Learning: Pong From Pixels tutorial. One thing is for sure: when it comes to deep reinforcement learning, OpenAI is all-in.

Compressing Networks

|

Model Compression: The WinZip of

Neural Nets? |

While NVIDIA might be today’s king of Deep Learning Hardware, I can’t help the feeling that there is a new player lurking in the shadows. You see, GPU-based mining of bitcoin didn’t last very long once people realized the economic value of owning bitcoins. Bitcoin very quickly transitioned into specialized FPGA hardware for running the underlying bitcoin computations, and the FPGAs of Deep Learning are right around the corner. Will NVIDIA remain the King? I see a fork in NVIDIA's future. You can continue producing hardware which pleases both gamers and machine learning researchers, or you can specialize. There is a plethora of interesting companies like Nervana Systems, Movidius, and most importantly Google, that don’t want to rely on power-hungry heatboxes known as GPUs, especially when it comes to scaling already trained deep learning models. Just take a look at

Fathom by Movidius or the

Google TPU.

But the world has already seen the economic value of Deep Nets, and the “software” side of deep nets isn't waiting for the FPGAs of neural nets.

The software version of compressing neural networks is a very trendy topic. You basically want to take a beefy neural network and compress it down into smaller, more efficient model. Binarizing the weights is one such strategy. Student-Teacher networks where a smaller network is trained to mimic the larger network are already here. And don’t be surprised if within the next year we’ll see 1MB sized networks performing at the level of Oxford’s VGGNet on the ImageNet 1000-way classification task.

Summary from ICLR 2016's Deep Compression paper by Han et al.

This year's ICLR brought a slew of Compression papers, the three which stood out are listed below.

Deep Compression: Compressing Deep Neural Networks with Pruning, Trained Quantization and Huffman Coding. Song Han, Huizi Mao, and Bill Dally. In ICLR 2016. This paper won the Best Paper Award. See Han give the

Deep Compression talk.

Neural Networks with Few Multiplications. Zhouhan Lin, Matthieu Courbariaux, Roland Memisevic, Yoshua Bengio. In ICLR 2016.

8-Bit Approximations for Parallelism in Deep Learning. Tim Dettmers. In ICLR 2016.

Unsupervised Learning

Philip Isola presented a very Efrosian paper on using Siamese Networks defined on patches to learn a patch similarity function in an unsupervised way. This patch-patch similarity function was used to create a local similarity graph defined over an image which can be used to discover the extent of objects. This reminds me of the Object Discovery line of research started by Alyosha Efros and the MIT group, where the basic idea is to abstain from using class labels in learning a similarity function.

Isola et al: A Siamese network has shared weights and can be used for learning embeddings or "similarity functions."

Learning visual groups from co-occurrences in space and time Phillip Isola, Daniel Zoran, Dilip Krishnan, Edward H. Adelson. In ICLR 2016.

Isola et al: Visual groupings applied to image patches, frames of a video, and a large scene dataset.

Initializing Networks: And why BatchNorm matters

Getting a neural network up and running is more difficult than it seems. Several papers in ICLR 2016 suggested new ways of initializing networks. But practically speaking, deep net initialization is “essentially solved.” Initialization seems to be an area of research that truly became more of a “science” than an “art” once researchers introduced

BatchNorm into their neural networks.

BatchNorm is the butter of Deep Learning -- add it to everything and everything will taste better. But this wasn’t always the case!

In the early days, researchers had lots of problems with constructing an initial set of weights of a deep neural network such that the back propagation could learn anything. In fact, one of the reasons why the Neural Networks of the 90s died as a research program, is precisely because it was well-known that a handful of top researchers knew how to tune their networks so that they could start automatically learning from data, but the other research didn’t know all of the right initialization tricks. It was as if the “black magic” inside the 90s NNs was just too intense. At some point, convex methods and kernel SVMs because the tools of choice — with no need to initialize in a convex optimization setting, for almost a decade (1995 to 2005) researchers just ran away from deep methods. Once 2006 hit, Deep Architectures were working again with Hinton’s magical deep Boltzmann Machines and unsupervised pretraining. Unsupervised pretaining didn’t last long, as researchers got GPUs and found that once your data set is large enough (think ~2 million images in ImageNet), that simple discriminative back-propagation does work. Random weight initialization strategies and cleverly tuned learning rates were quickly shared amongst researchers once 100s of them jumped on the ImageNet dataset. People started sharing code, and wonderful things happened!

But designing new neural networks for new problems was still problematic -- one wouldn't know exactly the best way to set multiple learning rates and random initialization magnitudes. But researchers got to work, and a handful of solid hackers from Google found out that the key problem was that poorly initialized networks were having a hard time flowing information through the networks. It’s as if layer N was producing activations in one range and the subsequent layers were expecting information to be of another order of magnitude. So Szegedy and Ioffe from Google proposed a simple “trick” to whiten the flow of data as it passes through the network. Their trick, called “BatchNorm” involves using a normalization layer after each convolutional and/or fully-connected layer in a deep network. This normalization layer whitens the data by subtracting a mean and dividing by a standard deviation, thus producing roughly gaussian numbers as information flows through the network. So simple, yet so sweet.

The idea of whitening data is so prevalent in all of machine learning, that it’s silly that it took deep learning researchers so long to re-discover the trick in the context of deep nets.

Data-dependent Initializations of Convolutional Neural Networks Philipp Krähenbühl, Carl Doersch, Jeff Donahue, Trevor Darrell. In ICLR 2016. Carl Doersch, a fellow CMU PhD, is going to DeepMind, so there goes another point for DeepMind.

Backprop Tricks

Injecting noise into the gradient seems to work. And this reminds me of the common grad student dilemma where you fix a bug in your gradient calculation, and your learning algorithm does worse. You see, when you were computing the derivative on the white board, you probably made a silly mistake like messing up a coefficient that balances two terms or forgetting an additive / multiplicative term somewhere. However, with a high probability, your “buggy gradient” was actually correlated with the true “gradient”. And in many scenarios, a quantity correlated with the true gradient is better than the true gradient. It is a certain form of regularization that hasn’t been adequately addressed in the research community.

What kinds of “buggy gradients” are actually good for learning? And is there a space of “buggy gradients” that are cheaper to compute than “true gradients”? These “FastGrad” methods could speed up training deep networks, at least for the first several epochs. Maybe by ICLR 2017 somebody will decide to pursue this research track.

Adding Gradient Noise Improves Learning for Very Deep Networks. Arvind Neelakantan, Luke Vilnis, Quoc V. Le, Ilya Sutskever, Lukasz Kaiser, Karol Kurach, James Martens. In ICLR 2016.

Robust Convolutional Neural Networks under Adversarial Noise Jonghoon Jin, Aysegul Dundar, Eugenio Culurciello. In ICLR 2016.

Attention: Focusing Computations

Attention-based methods are all about treating different "interesting" areas with more care than the "boring" areas. Not all pixels are equal, and people are able to quickly focus on the interesting bits of a static picture. ICLR 2016's most interesting "attention" paper was the Dynamic Capacity Networks paper from

Aaron Courville's group at the University of Montreal.

Hugo Larochelle, another key researcher with strong ties to the Deep Learning mafia, is now a Research Scientist at Twitter.

Dynamic Capacity Networks Amjad Almahairi, Nicolas Ballas, Tim Cooijmans, Yin Zheng, Hugo Larochelle, Aaron Courville. In ICLR 2016.

The “ResNet trick”: Going Mega Deep because it's Mega Fun

We saw some new papers on the new “ResNet” trick which emerged within the last few months in the Deep Learning Community. The ResNet trick is the “Residual Net” trick that gives us a rule for creating a deep stack of layers. Because each residual layer essentially learns to either pass the raw data through or mix in some combination of a non-linear transformation, the flow of information is much smoother. This “control of flow” that comes with residual blocks, lets you build VGG-style networks that are quite deep.

Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning Christian Szegedy, Sergey Ioffe, Vincent Vanhoucke. In ICLR 2016.

Resnet in Resnet: Generalizing Residual Architectures Sasha Targ, Diogo Almeida, Kevin Lyman. In ICLR 2016.

Deep Metric Learning and Learning Subcategories

A great paper, presented by Manohar Paluri of Facebook, focused on a new way to think about deep metric learning. The paper is “Metric Learning with Adaptive Density Discrimination” and reminds me of my own research from CMU. Their key idea can be distilled to the “anti-category” argument. Basically, you build into your algorithm the intuition that not all elements of a category C1 should collapse into a single unique representation. Due to the visual variety within a category, you only make the assumption that an element X of category C is going to be similar to a subset of other Cs, and not all of them. In their paper, they make the assumption that all members of category C belong to a set of latent subcategories, and EM-like learning alternates between finding subcategory assignments and updating the distance metric. During my PhD, we took this idea even further and build Exemplar-SVMs which were the smallest possible subcategories with a single positive “exemplar” member.

Manohar started his research as a member of the FAIR team, which focuses more on R&D work, but metric learning ideas are very product-focused, and the paper is a great example of a technology that seems to be "product-ready." I envision dozens of Facebook products that can benefit from such data-derived adaptive deep distance metrics.

Metric Learning with Adaptive Density Discrimination. Oren Rippel, Manohar Paluri, Piotr Dollar, Lubomir Bourdev. In ICLR 2016.

Deep Learning Calculators

LSTMs, Deep Neural Turing Machines, and what I call “Deep Learning Calculators” were big at the conference. Some people say, “Just because you can use deep learning to build a calculator, it doesn’t mean you should." And for some people, Deep Learning is the Holy-Grail-Titan-Power-Hammer, and everything that can be described with words should be built using deep learning components. Nevertheless, it's an exciting time for Deep Turing Machines.

The winner of the Best Paper Award was the paper, Neural Programmer-Interpreters by Scott Reed and Nando de Freitas. An interesting way to blend deep learning with the theory of computation. If you’re wondering what it would look like to use Deep Learning to learn quicksort, then check out their paper. And it seems like Scott Reed is going to Google DeepMind, so you can tell where they’re placing their bets.

Neural Programmer-Interpreters. Scott Reed, Nando de Freitas. In ICLR 2016.

Another interesting paper by some OpenAI guys is “Neural Random-Access Machines” which is going to be another fan favorite for those who love Deep Learning Calculators.

Neural Random-Access Machines. Karol Kurach, Marcin Andrychowicz, Ilya Sutskever. In ICLR 2016.

Computer Vision Applications

Boundary detection is a common computer vision task, where the goal is to predict boundaries between objects. CV folks have been using image pyramids, or multi-level processing, for quite some time. Check out the following Deep Boundary paper which aggregates information across multiple spatial resolutions.

Pushing the Boundaries of Boundary Detection using Deep Learning Iasonas Kokkinos, In ICLR 2016.

A great application for RNNs is to "unfold" an image into multiple layers. In the context of object detection, the goal is to decompose an image into its parts. The following figure explains it best, but if you've been wondering where to use RNNs in your computer vision pipeline, check out their paper.

Learning to decompose for object detection and instance segmentation Eunbyung Park, Alexander C. Berg. In ICLR 2016.

Dilated convolutions are a "trick" which allows you to increase your network's receptive field size and scene segmentation is one of the best application domains for such dilations.

Multi-Scale Context Aggregation by Dilated Convolutions Fisher Yu, Vladlen Koltun. In ICLR 2016.

Visualizing Networks

Two of the best “visualization” papers were “Do Neural Networks Learn the same thing?” by

Jason Yosinski (now going to

Geometric Intelligence, Inc.) and “Visualizing and Understanding Recurrent Networks” presented by Andrej Karpathy (now going to

OpenAI). Yosinski presented his work on studying what happens when you learn two different networks using different initializations. Do the nets learn the same thing? I remember a great conversation with Jason about figuring out if the neurons in network A can be represented as linear combinations of network B, and his visualizations helped make the case. Andrej’s visualizations of recurrent networks are best consumed in presentation/blog form[2]. For those of you that haven’t yet seen Andrej’s analysis of Recurrent Nets on Hacker News, check it out

here.

Convergent Learning: Do different neural networks learn the same representations? Yixuan Li, Jason Yosinski, Jeff Clune, Hod Lipson, John Hopcroft. In ICLR 2016. See

Yosinski's video here.

Visualizing and Understanding Recurrent Networks Andrej Karpathy, Justin Johnson, Li Fei-Fei. In ICLR 2016.

Do Deep Convolutional Nets Really Need to be Deep (Or Even Convolutional)?

|

| Figure from Do Nets have to be Deep? |

This was the key question asked in the paper presented by Rich Caruana. (Dr. Caruana is now at Microsoft, but I remember meeting him at Cornell eleven years ago) Their papers' two key results which are quite meaningful if you sit back and think about them. First, there is something truly special about convolutional layers that when applied to images, they are significantly better than using solely fully connected layers -- there’s something about the 2D structure of images and the 2D structures of filters that makes convolutional layers get a lot of value out of their parameters. Secondly, we now have teacher-student training algorithms which you can use to have a shallower network “mimic” the teacher’s responses on a large dataset. These shallower networks are able to learn much better using a teacher and in fact, such shallow networks produce inferior results when the are trained on the teacher’s training set. So it seems you get go [Data to MegaDeep], and [MegaDeep to MiniDeep], but you cannot directly go from [Data to MiniDeep].

Do Deep Convolutional Nets Really Need to be Deep (Or Even Convolutional)? Gregor Urban, Krzysztof J. Geras, Samira Ebrahimi Kahou, Ozlem Aslan, Shengjie Wang, Rich Caruana, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Matthai Philipose, Matt Richardson. In ICLR 2016.

Another interesting idea on the [MegaDeep to MiniDeep] and [MiniDeep to MegaDeep] front,

Net2Net: Accelerating Learning via Knowledge Transfer Tianqi Chen, Ian Goodfellow, Jonathon Shlens. In ICLR 2016.

Language Modeling with LSTMs

There was also considerable focus on methods that deal with large bodies of text. Chris Dyer (who is supposedly also going to DeepMind), gave a keynote asking the question “Should Model Architecture Reflect Linguistic Structure?” See

Chris Dyer's Keynote video here. Some of his key take-aways from comparing word-level embedding vs character-level embeddings is that for different languages, different methods work better. For languages which have a rich syntax, character-level encodings outperform word-level encodings.

Improved Transition-Based Parsing by Modeling Characters instead of Words with LSTMs Miguel Ballesteros, Chris Dyer, Noah A. Smith. In Proceedings of EMNLP 2015.

An interesting approach, with a great presentation by Ivan Vendrov, was “Order-Embeddings of Images and Language" by Ivan Vendrov, Ryan Kiros, Sanja Fidler, and Raquel Urtasun which showed a great intuitive coordinate-system-y way for thinking about concepts. I really love these coordinate system analogies and I’m all for new ways of thinking about classical problems.

Order-Embeddings of Images and Language Ivan Vendrov, Ryan Kiros, Sanja Fidler, Raquel Urtasun. In ICLR 2016.

See Video here.

Training-Free Methods: Brain-dead applications of CNNs to Image Matching

These techniques use the activation maps of deep neural networks trained on an ImageNet classification task for other important computer vision tasks. These techniques employ clever ways of matching image regions and from the following ICLR paper, are applied to smart image retrieval.

Particular object retrieval with integral max-pooling of CNN activations. Giorgos Tolias, Ronan Sicre, Hervé Jégou. In ICLR 2016.

This reminds me of the RSS 2015 paper which uses ConvNets to match landmarks for a relocalization-like SLAM task.

Place Recognition with ConvNet Landmarks: Viewpoint-Robust, Condition-Robust, Training-Free. Niko Sunderhauf, Sareh Shirazi, Adam Jacobson, Feras Dayoub, Edward Pepperell, Ben Upcroft, and Michael Milford. In RSS 2015.

Gaussian Processes and Auto Encoders

Gaussian Processes used to be quite popular at NIPS, sometimes used for vision problems, but mostly “forgotten” in the era of Deep Learning. VAEs or Variational Auto Encoders used to be much more popular when pertaining was the only way to train deep neural nets. However, with new techniques like adversarial networks, people keep revisiting Auto Encoders, because we still “hope” that something as simple as an encoder / decoder network should give us the unsupervised learning power we all seek, deep down inside. VAEs got quite a lot of action but didn't make the cut for today's blog post.

Geometric Methods

Overall, very little content pertaining to the SfM / SLAM side of the vision problem was present at ICLR 2016. This kind of work is very common at CVPR, and it's a bit of a surprise that there wasn't a lot of Robotics work at ICLR. It should be noted that the techniques used in SfM/SLAM are more based on multiple-view geometry and linear algebra than the data-driven deep learning of today.

Perhaps a better venue for Robotics and Deep Learning will be the June 2016 workshop titled

Are the Sceptics Right? Limits and Potentials of Deep Learning in Robotics. This workshop is being held at RSS 2016, one of the world's leading Robotics conferences.

Part III: Quo Vadis Deep Learning?

Neural Net Compression is going to be big -- real-world applications demand it. The algos guys aren't going to wait for TPU and VPUs to become mainstream. Deep Nets which can look at a picture and tell you what’s going on are going to be inside every single device which has a camera. In fact, I don’t see any reason why all cameras by 2020 won’t be able to produce a high-quality RGB image as well as a neural network response vector. New image formats will even have such “deep interpretation vectors” directly saved alongside the image. And it's all going to be a neural net, in one shape or another.

OpenAI had a strong presence at ICLR 2016, and I feel like every week a new PhD joins OpenAI. Google DeepMind and Facebook FAIR had a large number of papers. Google demoed a real-time version of deep-learning based style transfer using TensorFlow. Microsoft is no longer King of research. Startups were giving out little toys -- Clarifai even gave out free sandals. Graduates with well-tuned Deep Learning skills will continue being in high-demand, but once the next generation of AI-driven startups emerge, it is only those willing to transfer their academic skills into a product world-facing focus, aka the upcoming wave of deep entrepreneurs, that will make serious $$$.

Research-wise, arXiv is a big productivity booster. Hopefully, now you know where to place your future deep learning research bets, have enough new insights to breath some inspiration into your favorite research problem, and you've gotten a taste of where the top researchers are heading. I encourage you to turn off your computer and have a white-board conversation with your colleagues about deep learning. Grab a friend, teach him some tricks.

I'll see you all at CVPR 2016. Until then, keep learning.

Related computervisionblog.com Blog Posts

Why your lab needs a reading group. May 2012

ICCV 2015: 21 Hottest Research Papers December 2015

Deep Down the Rabbit Hole: CVPR 2015 and Beyond June 2015

The Deep Learning Gold Rush of 2015 November 2015

Deep Learning vs Machine Learning vs Pattern Recognition March 2015

Deep Learning vs Probabilistic Graphical Models April 2015

Future of Real-time SLAM and "Deep Learning vs SLAM" January 2016

Relevant Outside Links

[1]

Welcome to the AI Conspiracy: The 'Canadian Mafia' Behind Tech's Latest Craze @ <re/code>

[2]

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks @ Andrej Karpathy's Blog

[3]

Deep Learning for Robots: Learning from Large-Scale Interaction. @ Google Research Blog